6 A note on notebooks

The next chapter is the first of a series of chapters that are generated from Jupyter Notebooks.

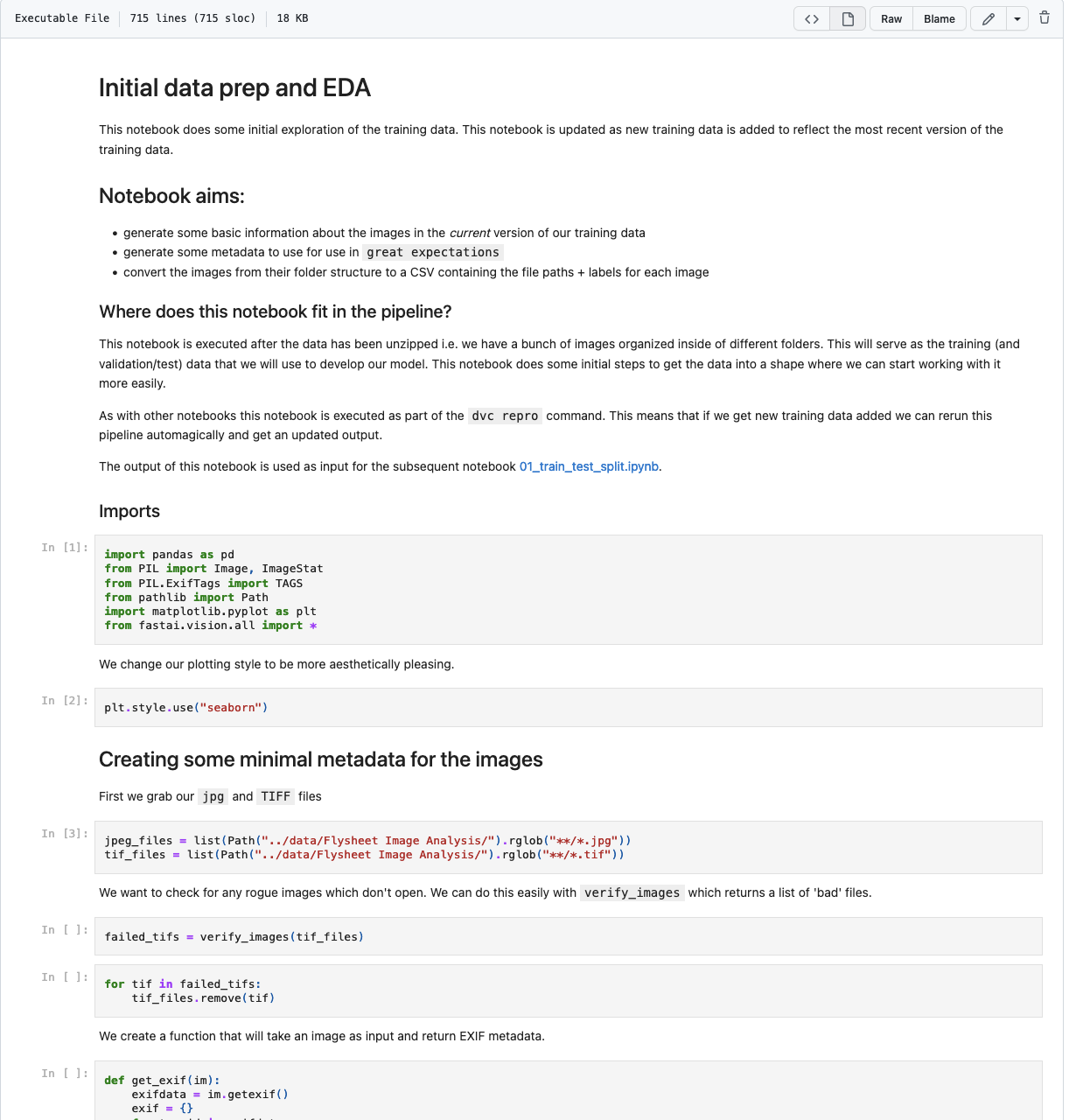

Jupyter Notebooks are a programming environment that allows you to combine code, prose, and output images in a single document. This can make a notebook a powerful tool for communicating with others.

Sometimes notebooks are created to allow others to rerun the notebook and get the same results. This is not our goal here. Instead, we share these notebooks largely to illustrate our approach at a particular point in time and as a way of discussing some important concepts.

6.1 How we (originally) executed our notebooks?

Whilst these notebooks weren’t designed to be run outside of our use case we did make some effort, in particular early on during our project to make our work slightly more “reproducible”. In particular, we used a tool called DVC to organize our notebooks into a ‘pipeline’ that could be executed from a single command. This meant that as we updated the data entering all the other steps we could easily update the later stages of the process which depend on this process. This made it easier in the early stages of this project to iterate on the process.

We’ll talk more about this aspect in a later chapter on tooling.

True reproducibility is not always that easy to achieve in machine learning. We usually think of computers as being fairly predictable when given the same input. For example the following python code,

>>>grades = [88, 90, 80]

>>>mean_grade = sum(grades)/len(grades)

>>>print(mean_grade)

86shouldn’t change. However, there is quite a bit of potential randomness in machine-learning models that can result in different outputs occurring for code that appears to be the same. There are ways of trying to get around this but we flag this to be clear about what we mean here.